Originally Posted: http://www.daggerpress.com/2010/04/16/kick-ass-tests-the-limits-of-exploitainment/print

Posted By Adam Mehring On April 16, 2010 @ 3:37 am In Featured, Movies, Pop & Culture | 35 Comments

A touch more than 70 years ago, Gone with the Wind kicked up controversy for its use of what was considered profane language. The line in question, of course, is now a ubiquitous cinematic staple, frequently repeated without hesitation. Frankly, no one really gives a damn about it anymore.

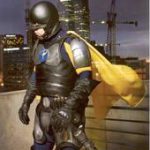

Kick-Ass makes its way into theaters this weekend, bearing a title that would have sparked considerable outrage on its own back in the days of Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh, and the Motion Picture Production Code’s stringent censorship regulations.

The title would have boiled blood. The film itself would have caused massive coronaries.

Kick-Ass proudly and quite audaciously features absurdly graphic violence and crude language guised by a sunny demeanor, vivid colors, and the appeal of superhero mythology.

At the peak of its depravity is “Hit Girl,” a pint-sized killing machine with the proficiency of some terribly powerful ninja master, donning a purple wig and cape or a schoolgirl outfit and pigtails—and just eleven years old. She smiles wryly, even sweetly, before driving her blade through the heart of an offender, or converting an opponent’s body into a bullet-riddled corpse.

Any sense of childlike abandonment she may yet possess is swiftly dispelled when she opens her mouth, unleashing obscenities as if they were mere yawns. Hit Girl even has the distinction of speaking the obligatory single “c-word” of the hard R-rated film, just as she verbally likens her cohorts to a specific feminine hygiene product (a “d-word” this time).

Hit Girl’s unexpected coarseness is effectively—very effectively—shocking. Whether the initial shock is followed by enjoyment, disgust, or some combination of the two is the point at issue.

As a character, her existence is a mightily depressing one: led by her father and fellow crime-buster “Big Daddy” (Nicholas Cage) through a life entirely devoted to deadly maneuvers and vigilante justice. When Big Daddy purposefully fires a round into his daughter’s torso to let her experience its physical impact, Hit Girl’s bullet-proof vest cannot protect her innocence from shattering into a million pieces.

The film does acknowledge the tragedy that Hit Girl has been robbed of her childhood but only with the passing deference of any issue brought up in a comic book caper. She is certainly no worse off because of her circumstances, nor does she seem to miss the freedoms of being a normal little girl.

On the same token, Hit Girl’s precocious antics are humorous in a disbelieving sort of way, and watching her massacre bad guys through increasingly improbable, ridiculous, and gloriously bloody methods proves quite exciting.

But the wasted innocence of a fictional character is not really what is at stake here. Hit Girl is played by Chloë Grace Moretz, a promising young performer on a serious spunky streak after 500 Days of Summer last year and, recently, Diary of a Wimpy Kid.

Hit Girl is lifted from a comic book, but Moretz, believe it or not, is a real human being who, at the age of twelve, had to really say the “c-word” and really participate in the graphic, albeit staged, sequences of violence. It is Moretz’s innocence that is potentially sacrificed by Kick-Ass, and no part of that is the slightest bit entertaining.

Of course, this is not the first time that filmmaking has exposed child actors to unduly explicit environments. In 1978, Director Louis Malle drew heat for his film Pretty Baby, in which a twelve year-old Brooke Shields played a child prostitute and appeared completely nude. Luc Besson caused a quieter commotion with 1994’s The Professional, placing a young Natalie Portman at the center of a murdering spree and sexual objectification.

Anna Paquin won a Best Supporting Actress Oscar at the age of eleven for her performance in Jane Campion’s The Piano, a film that featured nudity and graphic sex. However, Paquin was not involved in any of these scenes, and her father reportedly did not allow her to see the film in its entirety.

Distributor Lionsgate attempts to rationalize Moretz’s involvement with Kick-Ass by passing the film off as harmless fantasy. Her mother is described reminding the cast and crew, “It’s Hit Girl saying it, not my daughter,” in reference to that certain “c-word.” Meanwhile, director Matthew Vaughn has apparently crafted something “otherworldly,” a “comic book universe” with “hyper-real” violence that is “a signature of the revenge-fantasy genre in which the film is solidly steeped.”

Here’s the problem with that assertion: the principle conceit of Kick-Ass is that it takes place in our world—that a normal person without any special abilities decides to strap on a scuba suit and fight injustice in a society—our society—accustomed to looking the other way.

The film’s central character, “Kick-Ass” himself (Aaron Johnson), gains notoriety after a video of him facing off with a group of muggers goes viral on YouTube. He then uses a MySpace account to communicate with citizens in need of a superhero’s assistance. When “Red Mist,” another makeshift costumed avenger of sorts, docks his iPod onto the dashboard of his modified Ford Mustang, the supposed “otherworldly” setting of Kick-Ass seems particularly our-worldly, or at least embedded with a suspicious amount of familiar technology.

Eventually, the film does concede more of its connection to reality in favor of stylized violence and fanciful plot constructs—Hit Girl’s destructive rampages included—but it does so against its director’s own intentions, and while defying its previously established logic.

Vaughn wants to have it both ways: to ground his film in reality and partake in decadent fantasy. And so, ultimately, Kick-Ass transpires on the untilled fields of a fanboy’s paramount dreamscape.

Even as Lionsgate assures us of this notion—that no reality they endorse would include a gun-slinging middle-schooler spewing four-letter words—the studio has fostered the realism angle in its promotional push for the film. Real Life Superheroes.org [2], a website devoted to inspiring and chronicling masked crusaders in the real world, has become little more than a multi-tiered advertising platform for Kick-Ass.

Lionsgate does not claim ownership to the site—only to a coordinated campaign. However, the domain was not registered until January, 2009, three months after Kick-Ass began principal production, and otherwise lacks an internet footprint. A case of coincidental, simultaneous, and identical inspiration on the part of the Kick-Ass creative team and a group of genuinely concerned citizens, or thinly-veiled astroturfing at its most nauseating?

Either way, Real Life Superheroes.org claims not to endorse vigilantism but then provides links to several sex offender registries, local crime databases, and listings from America’s Most Wanted, along with more links to individual state laws on carrying weapons and making citizen’s arrests—all under the suggestive heading of “FIGHT crime.” Surely, this is not a practical or helpful way to shape up society (just to boost awareness for an upcoming movie about “real life superheroes”), but Lionsgate offers its stamp of approval just the same.

The publicized advertising blitz for Kick-Ass portrays masked heroes on brightly colored posters, images that are sure to appeal to younger crowds drawn to classic superhero iconography. Following the screening I attended, a boy no older than Hit-Girl wearing a “Kick-Ass” novelty tee-shirt trudged out of the theater with a sullen look on his face and his father, also vested in “Kick-Ass” branded swag, looking astonished right behind him. One or both of them had clearly just been duped, but seeing that confused, wandering ghost of a boy—he, too, robbed of his innocence, I imagined—was a little bit devastating.

Posters hung in cinema lobbies create a dilemma for certain theatergoers: so long as Kick-Ass is around, you can’t take a child to a G-rated movie without exposing them to content—to a word—that would automatically earn any film a PG rating. The same word, the film’s very title, is repeated on billboards, television commercials, merchandise, and, yes, tee-shirts for anyone to see.

On the other hand, far more inappropriate content can be just as readily found on magazine covers in the check-out lanes of grocery stores (the latest issue of Cosmopolitan boasts in bold face “The 7 Best Orgasm Tricks in the World!”), during beer commercials, and in Miley Cyrus music videos.

Moral implications and dubious marketing strategies aside, as an exercise in entertainment and filmmaking efficiency, Kick-Ass, for me, just barely squeaks by as something that can qualify as artistic expression—a crude, violent, absurd, and vulgar artistic expression. The film manages to maintain enough levity in its narrative and luster in its presentation to pass as escapist entertainment—crude, violent, absurd, and vulgar escapist entertainment.

Ironically, Vaughn’s failure to convince us that Kick-Ass takes place in our reality or any relatable setting is what salvages the film. Had Hit-Girl seemed slightly more human, her indiscretions would have been unequivocally reprehensible. Instead, she is, as is most of Kick-Ass, an outrageous cartoon brought to life.

For this reason, the film is no more offensive, even less offensive, than last year’s eight-times Oscar-nominated film Inglourious Basterds (sporting another lamentable title), in which director Quentin Tarantino wagered his crude, bloodthirsty revenge fantasy on a sensitive historical issue for stronger dramatic impact. By my estimation, that embraces the very definition of exploitation. As does the WE “reality” show Little Miss Perfect, parading three and four-year-olds around in their disturbingly skimpy “wow-wear.” Kick-Ass is certainly no more destructive than that.

To be honest, I can’t recall the last time I felt such strong and varied emotions while watching a movie as I did during Kick-Ass. Providing moments of shock, horror, disgust, excitement, intensity, hilarity, and general absurdity, Kick-Ass is a rollercoaster ride—a swift kick in the pants, ahem, in the ass, perhaps.

As a film—as an artistic expression and means of entertainment (for those of the proper age and condition)—I have to give Kick-Ass…

As a greater reflection of morality and decency in our culture, Kick-Ass gives me reason to worry.